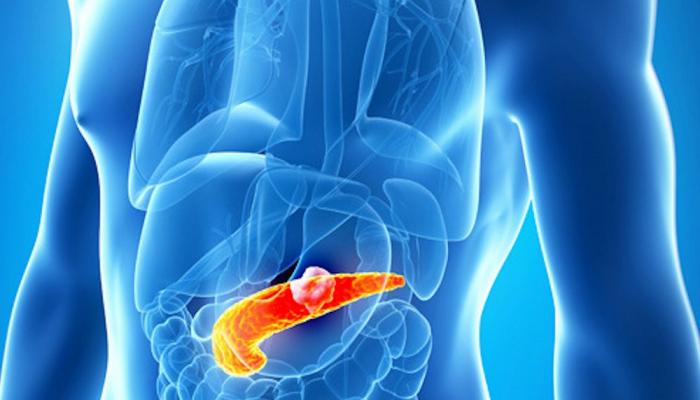

- In type 2 diabetes, the quantities of insulin the body produces to regulate blood sugar levels are insufficient.

- A new lab-based study suggests a surprising role of fat in maintaining insulin production by the pancreas in conditions of excess sugar.

- A cycle of fat storage and mobilization in the pancreas may preserve the organ’s ability to make insulin.

- The finding could explain how intermittent fasting might help prevent and treat type 2 diabetes.

Insulin is a hormone that the pancreas produces to regulate the amount of sugar circulating in the blood. In diabetes, this regulatory mechanism starts to break down either when the pancreas fails to produce enough insulin or when the body’s tissues become resistant to the hormone’s effects. Over time, uncontrolled high blood sugar resulting from diabetes can lead to blindness, kidney failure, strokes, and lower limb amputation. According to the World Health Organization (WHO)Trusted Source , in 2019, diabetes caused 1.5 million deaths worldwide. More than 95% of people with diabetes have types 2 deabetes, which is largely the result of physical inactivity and excess body weight. Scientists have reached a consensus that high blood sugar levels damage beta cells in the pancreas — the cells that make insulin — but the part that fat plays is more controversial. Findings from a new lab-based study suggest that fat stores in the pancreas may help maintain insulin secretion and slow the onset of diabetes. This research may provide a possible explanation for the benefits of exercise and intermittent fasting as strategies to prevent and treat type 2 diabetes. The study indicates that a cycle of fat storage in pancreas cells after mealtimes, followed by the breakdown of fat in the hours before the next meal, may help maintain insulin production. The research, led by scientists at the University of Geneva Medical Centre in Switzerland, appears in the journal Diabetologia. The scientists exposed human and rat beta cells to periods of excess sugar, with or without high fat levels. As expected, over time, high sugar levels reduced the cells’ ability to secrete insulin, compared with normal sugar levels. However, an abundant supply of fat appeared to protect the beta cells’ insulin secretion against the effects of high sugar levels.

“When cells are exposed to both too much sugar and too much fat, they store the fat in the form of droplets in anticipation of less prosperous times,”Lucie Oberhauser, Ph.D. , first author of the study, explains. “Surprisingly, we have shown that this stock of fat, instead of worsening the situation, allows insulin secretion to be restored to near-normal levels,” she adds.

The researchers observed that periods of high fat and sugar availability, alternating with low availability, activated genes in pancreatic cells that promoted a cycle of fat storage and mobilization. The benefits of this cycle became apparent during periods when the cells no longer had ample energy supplies. “These fasting-like conditions induced fat mobilization that supported insulin secretion,” said Pierre Maechler, Ph.D., who led the study. In other words, the whole cycle of fat storage (overnutrition) followed by fat mobilization (fasting) is required for the mechanism uncovered in our study,” he told Medical News Today. He said a fast of just 4–6 hours would be sufficient to allow beta cells to reset and recover their insulin-secreting capacity between meals. “Practically, avoid snacking!” he advised. He believes that the release of fat from stores is not a problem provided the body uses it as a source of energy between mealtimes — for example, to fuel regular bouts of physical activity.